The city of Messina is in the top right corner of the island of Sicily, situated exactly where the ‘boot’ of mainland Italy is about to make contact and kick Sicily into the back of Spain’s net.

The above is an often-used analogy for the country’s geography, but I think it is a bad one. Rather than Italy having any resemblance to a football boot I think it looks more like a kinky boot. It’s got a six-inch heel for one thing (Puglia), and Italy is quite definitely thigh-high in length.

Although, if there were a footy tournament for drag-queens I can see it working.

That large heel may explain why very early references to the shape of Italy, pre-1600, don’t mention a boot at all, as nobody wore high-heeled boots or shoes. So, it wasn’t immediately obvious that Italy looked like the outline of any footwear, fetish or otherwise.

Although it could also have been because they had rubbish maps and football hadn’t been invented.

Kinky boots certainly hadn’t been invented back then, and if you’d dared to come up with a pair in Renaissance Italy you’d probably have been burned at the stake. There were strict laws regarding what you could wear in some Italian cities. This was to avoid the sins of pride and envy upsetting God, he was easily offended in those days. The wrong shade of green on a tunic, or too much fur trim on your knickers, could land you in big trouble with the authorities.

Interestingly three times as many men were convicted of such clothing offences than women. Italian men have always paraded around like peacocks, but this was a time when the Fashion Police really did exist.

High heeled boots only came along when 17th century Persian horsemen required them for a practical use. They needed something to hold their feet steady in the stirrups when they stood up in the saddle to fire arrows. So, high heels were first worn by men, before they became fashionable.

Although, when it comes to kinky boots, men have still got the larger share of the market with all their cross dressing and the purchasing of unwanted gifts from Ann Summers for their wives.

Given Messina’s proximity to the toe of Italy’s kinky boot, which is only three miles away across the Strait of Messina, the city has always been a busy port. As well as ferries and cargo going back and forth to the mainland, it now welcomes humungous cruise liners too.

Whereas the liners, and their contents, are a modern-day curse upon places where you could previously enjoy a quiet pint, Messina’s gateway location also means it has been blessed with the misfortune to be of strategic importance. Over its history many aggressive forces have either wanted to own it or destroy it.

First to plant their flag on Sicily were the Greeks, they were then ousted by the Carthaginians between 580 and 265 BC. The Carthaginians came from North Africa or, to be precise, what is now called Tunisia. This is only around eighty miles from the west of Sicily, so the Carthaginians didn’t need to travel far to grab some new real estate.

This relatively short hop from Tunisia also explains why Sicily, and its southern islands, have become the portal into Europe for those migrating from Africa in modern times. Despite it being no great distance in nautical terms, rickety and overcrowded small boats have meant thousands have drowned whilst attempting the crossing.

Indeed, this journey became so deadly, and undertaken by so many, that the Italian coastguard started unloading migrants from their boats fairly soon after they’d left the African coast. The people smugglers, nice folks that they are, saw this merciful act as a cost saving for them as they only had to fuel the boats with enough petrol to get them halfway.

Rather than looking for asylum and a better life, the original North African migrants, the Carthaginians, had more hostile intentions. They eventually made it eastward across Sicily to the Strait of Messina. It was here they attracted the attention of an up and coming force on the mainland, the Romans.

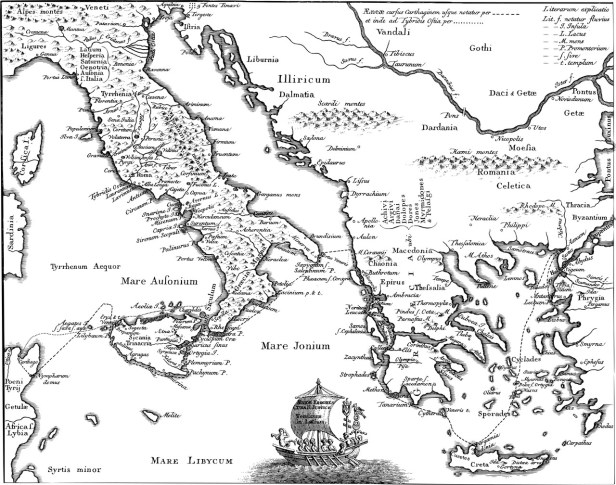

The Romans could have given their new neighbours a friendly wave from across the water, see how close it is in the picture, but they took the incursion personally and the resulting contretemps started the First Punic War in 264 BC. The wars were so called because the Carthaginians, although they had settled in North Africa, were originally Phoenicians from the Middle East. Phoenicia is ‘Punica’ in Latin.

There would go on to be three Punic Wars, and they would last over a hundred years. The Romans won 3-0. Any chance of another fixture was snuffed out when the Romans totally obliterated Carthage after the last of the wars. There’s nothing like a sore winner.

Over the following centuries, Messina would then be Roman, Greek-Byzantine, Arab, Norman and Spanish, with a few other occupiers, rivals and enemies thrown in. It finally became ‘Italian’, along with the rest of Sicily, in 1861. In fact, all of Italy’s independent states become ‘Italy’ around then, it’s a very young country.

Despite all these invaders, Messina’s most deadly adversary has always been Mother Nature.

I wonder if a lot of day-trippers that go for a wander around Messina think what a nice old city it is; charming piazzas, lovely churches and a cathedral with a bell tower that features an astronomical clock. The reality is that most of the city only dates from 1909 onwards.

The narrow Strait of Messina holds a lethal secret in its depths, and we’re not talking sneaky jellyfish with long stingers or cantankerous sharks feeling peckish. It has a fault line in the earth’s crust running the length of it. You may be aware that a lot of Southern Italy, including Sicily, is very geologically active. For one thing, there are more volcanoes than you can shake a big stick at, although I wouldn’t get too close with the stick. Those volcanoes go pop quite regularly.

All of this is because the affected areas sit at the boundary of the African and Eurasian tectonic plates. Like those modern migrants, the African plate is desperately trying to move north. It continuously barges and pushes into the Eurasian plate, hence those volcanoes erupting through all the cracks and rifts this movement causes.

Incidentally, there is not much point in the migrants waiting on a Tunisian beach for the land to give them a safer ride to Europe, the African plate only moves at 2.15 cm per year. So, it would take 6 million years to get to Sicily. This is assuming Sicily hadn’t moved north on top of its own plate by then, which it may well have done. In which case those patient migrants would have wasted their time.

All these fissures and faults caused by plate movements have resulted in some major issues in the past, for instance you wouldn’t have wanted to be holidaying at the lovely seaside resort of Pompeii in AD79.

The fault-line that runs up the Strait of Messina has been a particular pain in the arse to the city of Messina over many centuries. This is because it makes the area very prone to earthquakes, and enormous ones at that.

On December 28th 1908, at 5.20am, a huge earthquake struck Messina. 75,000 were killed and over 90% of the buildings were either destroyed or damaged beyond repair. The death toll was so high because most of the residents were still snoozing in their beds as their houses collapsed on top of them.

This wasn’t the end of it though, ten minutes later the sea suddenly receded and a tsunami swept in with waves 12m high. A lot of panicking folks in their pyjamas had fled to the relative safety of the seafront, so the tsunami claimed another 2,000 lives.

The Messina disaster remains Europe’s most deadly earthquake. At the time, it was big news all around the world and donations and offers of homes for refugees came from as far away as the USA.

It was also the first major earthquake to be recorded by scientific instruments, hence how modern-day seismologists have been able to work out how it happened and where the fault lay, if you’ll excuse the pun.

Therefore, what you see in Messina now is all relatively modern, either new buildings or reconstructions. The Cathedral, for instance, was mostly reduced to rubble and had to be rebuilt. The one remaining 14th century mosaic is in the apse to the left of the altar. It is the Virgin and Child on a shimmering golden background.

You can tell it is important as it’s the only mosaic you can illuminate for one euro to get a decent picture. The others are all recent reconstructions, but at least they don’t have the temerity to charge you for lighting those up. They still want a euro to light a tealight candle though.

Hint: It’s cheaper to buy a big bag of tealights from IKEA and smuggle your own in. That’s if you do a lot of candle-lighting in churches or have a lot of folks to light candles for and don’t want to miss anyone out, lest they don’t speak to you when you get to Heaven.

The cathedral’s bell tower has the biggest and most complex astronomical clock in the world. Numerous cavalcades of animated figures start doing their thing at 12 noon every day. The latter would have been handy to know, seeing as I arrived at 12.30. Feeling somewhat robbed I elected to pay a few euros to climb up the inside of the tower to see all the mechanisms and animatronics behind the show.

Interesting though they were, it was a little like taking a tour of some dead fireworks the morning after you’d missed a massive public display. Close, but no cigar.

The clock was built and installed in the reconstructed tower in 1933, by a French company. Therefore, it is now almost a hundred years old, but so is Morden Tube Station near where I live. Apart from railway nerds, I don’t expect to see coachloads of tourists flocking to South London to see it any time soon, unless the KFC opposite is having a sale. A hundred years old is nothing special nowadays, we were well into the timeframe of building prolifically as our cities grew much bigger.

I am being a little unfair to Messina, I did like the place and they’ve done their best to patch up and make do. Some of the reconstructions are quite convincing, and they would probably fool most visitors who didn’t read the small print.

Apparently, some of the temporary housing that was built after the earthquake to house survivors was still being used up until only a few years ago. It had done well, as Messina was also heavily bombed by the Allied Forces in WWII. This time the curse of its strategic location laid it open to another flattening.

One of the reasons the damage was so extensive in 1908, apart from the Messina’s proximity to the epicentre, was that the historic old town buildings were not built to withstand earthquakes.

Messina has two very important paintings by Caravaggio from around 1609. He painted them in Sicily after scuttling from Rome, and then being kicked out of Malta. He’d been on the run following the trivial matter of murdering someone in Rome.

The paintings are housed in a modern and very solid looking museum which is a couple of miles outside the city. Presumably its remote location being further away from the troublesome fault line, and also any other big buildings that might fall on top of it. There’s nothing worse than a crushed Caravaggio, especially if you can’t afford to buy another one. Southern Italy has always been the poor relation of the likes of Rome and Milan.

The museum is out of the range of most day-trippers to the city. It is troublesome to get to for one thing, being half an hour away on a crowded bus from near the cathedral. That’s assuming you can find the stupid bus-stop in the first place on an incomprehensible local travel app, which is in Italian. English isn’t widely spoken in Southern Italy. Then again, Italian isn’t widely spoken in South London, so I can’t grumble.

You can understand the city’s caution in protecting some of its most valuable assets, even if visitors do have to make an extra effort to see them. On the plus side, I had those hugely impressive Caravaggios all to myself, in fact I had pretty much the whole museum to myself. This may have explained why the café had closed early and why they asked me to lock up the museum when I left. I left the key under the mat.

Building in sensible locations and using low-level robust architecture are the clever things to do in a geologically volatile area. The ground beneath Messina isn’t sitting still, and it is only a matter of time before it all happens again. So why, might you ask, are they now planning to build the world’s longest suspension bridge across the Strait of Messina?

It is no small bridge; it will carry six lanes of traffic and two train lines from the Italian mainland to Sicily. The project has been on and off for thirty years and it has been stalled for a number of reasons. One of them was that it would disrupt bird migrations and another was that the project presented the mafia with a golden opportunity for corruption.

I can think of a much bigger reason why you wouldn’t want to build a massive bridge here, or maybe I’m missing something.

However, it is definitely going ahead and completion is expected by 2032. The cost is being written off as part of Italy’s contribution to NATO defence spending, a move which a disgruntled USA described as ‘creative accounting’.

The people of Messina aren’t too happy about the bridge either, and they recently held a big protest against it. If anyone can see the elephant in the room it is going to be them. Perhaps they should be listened to before it starts shitting everywhere.

It is of course possible that the bridge won’t be at risk of destruction when the next earthquake happens, modern civil engineering techniques are very clever. They also have the advantage of AI to help with the design. Perhaps the plan is smarter than I think, the bridge could act as a very cunning giant staple to pin the two sides of the fault line together.

Although I’m with the folks of Messina on this one, I think I’ll be taking the ferry.