For those of my generation, Belfast, in Northern Ireland, was synonymous with bombs, bricks and bullets. A warzone involving two rival factions with a complex history of religion and politics which had festered for decades and then erupted into violence in the late 1960s.

This wasn’t the Middle East, where these things normally kicked off, it was a bit closer to home, but it had a degree of geographic separation that meant we could still be appalled from the safety of our sofas as we watched this angry spectacle unfold on TV.

Of course, all that remoteness changed when the carnage spilled over onto the UK mainland with headline bombings in London, Birmingham and Manchester. For me, growing up in a small seaside resort on the east coast of England, it still remained a somewhat distant conflict. As some wag said at the time, ‘They wouldn’t bomb Cleethorpes, nobody would know they’d been there’.

So, Belfast had its ‘troubles’, and that was all I knew of the place. Naturally, I hoped Northern Ireland would sort itself out, especially as I was getting to the age where I would be leaving home and heading to a bigger town or city that had a university. Or even a polytechnic, if I really screwed things up. Which I did.

The consolation prize of a polytechnic still came with all my fees paid and a student grant, which was effectively free beer money so I’d planned to spend a lot of time in pubs and clubs. I didn’t want to waste most of that time looking under chairs and tables for suspect packages, or keeping a close eye on anybody with an Irish accent and a shopping bag.

In my later teens I was also becoming increasingly politically aware. My friends and fellow students had differing views on solutions to the problems of Northern Ireland, albeit touted from the security of our previously checked bar stools. However, the one thing my generation would have completely agreed on was…why the buggery would you ever want to go there?

Time moved on, and by the late 1990s discussions began to replace deaths and The Good Friday Agreement of 1998 brought a tentative end to three decades of bloody nonsense. Would I have gone to Belfast then? Nope, still a bit dodgy.

Fast forward another thirty years and would I go there now? I’d certainly moved on in how I viewed Northern Ireland, the troubles were no longer visibly troublesome, but a definite ‘nope’ had turned to a more lethargic ‘nah’. Apprehension had turned to apathy. This was because over the intervening period I’d travelled extensively, as you can tell from this website.

My mantra was, if it involved an aeroplane, then it would be much more interesting to go somewhere abroad rather just elsewhere in the UK. Why go through all that airport nonsense, and aircraft seating designed for Oompa-Loompas*, just to end up sitting in another Wetherspoons**?

However, I’d recently started thinking about places I hadn’t been. It struck me that in all my travels on this planet there was this one chunk of the United Kingdom, albeit squatting on someone else’s island, some might say, that I’d never visited.

So, I planned a trip to Belfast. It almost faltered at the final hurdle when I saw the outrageous price of the city’s hotel rooms, apparently there are just not enough of them. At times like these you can rely on the last refuge of the scoundrel, literally, which is Airbnb. Fortunately, the residents of Belfast haven’t taken to the streets yet to protest against holiday rental properties, as they have elsewhere in Europe. God forbid they ever do, given their previous form it could turn nasty.

The visit to Belfast turned out to be a ‘Road to Damascus’ experience for me, not in the sense that I was on my way to Damascus via Belfast, there are no direct flights, but in that it was a revelation. Incidentally, I think I’m okay in alluding to St Paul, both sides of the religious divide in Belfast consider him to be one of their gang. Now I come to think of it, I think they both follow the same God too. Makes you wonder what all the fuss was about on the religious front. If only the politics were so naively dismissed.

I had preconceptions of Belfast, very old ones I admit, but they still lingered deep in the subconscious. They weren’t really relevant to this revelation though, what was more interesting was that I was visiting a place I had little or no current knowledge of. A number of recent trips to other places had been repeat visits but this was somewhere new, and what a pleasant surprise it turned out to be. An invigorating experience that energised my travel beans.

After visiting Belfast I could wax lyrical about the wide and clean streets, the bars and pubs, and even the lovely comedy club where I couldn’t understand a word of the broad Northern Irish accent, which was funny its own way. However, I’ve never been anywhere with such friendly folk, which is what really makes it a very welcoming city. I’ve no idea what ‘side’ they were on, and I didn’t ask, but I’ve never been to a place where I haven’t a bad word to say about anybody***.

If you’ve read my other writings you’ll know I often end up falling out with someone, not in Belfast though. So lovely people aside, what else does this city have to offer? Admittedly, there was a little bit of dark tourism involved, actually quite a lot.

First up was a black cab tour of the northwest area of the city. Those of a certain age will recognise such names as The Falls Road (the Catholic side, road signs in English and Gaelic) and The Shankill Road (the Unionist side, more English than England). These predominantly working-class areas were synonymous with the troubles.

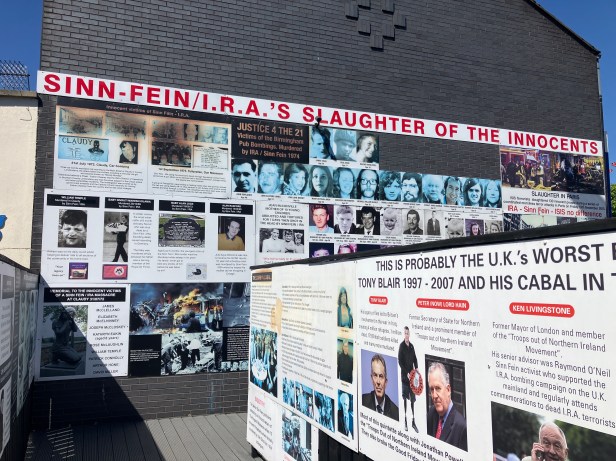

I mainly wanted to see the murals painted on the ends of rows of terraced houses in both areas; graphic representations of a production line of martyrs, political allegiances and ongoing grievances. The murals are still there, regularly repainted and buffed up. The troubles haven’t quite gone away, they’ve just gone quiet.

Indeed, there is still an obscene wall separating the two communities, ironically called The Peace Wall. I asked our guide why it is still there, the answer being that nobody dare take it down. A fragile peace, as evidenced by the gardens backing onto the wall having wire cages covering them to deflect any incoming bottles or bricks.

The next stop on our dark tourism trip was a ‘visitor experience’ dedicated to probably the most famous disaster ever, the Titanic. Quite why the Titanic remains such a fascination, over a hundred years after it sank, is a bit of an odd one. Maybe it was the inequity in the way the passengers were treated due to the pervading class system, or the lack of lifeboats that represented the unsinkable hubris of the White Star Line’s owners, or maybe it was Kate Winslet getting her kit off in the film. Whatever the obsession, we’ve had many more disasters and atrocities since then, and with casualties in the millions.

Unless you were going to build a floating exhibit in the middle of The Atlantic, then Belfast is probably the best place for something like this because the ship was built here. Indeed, the slipway it launched from abuts the back of the exhibition centre. Whilst ‘Titanic Belfast’ is probably one of the better visitor-experiences I’ve been to, I found the remnants of the slipway outside much more evocative. Although that might have been because, after three hours inside, it presented an excellent opportunity to top up some dangerously low nicotine levels.

The only grouse I had is that although they dedicate a fair amount of space to the rediscovery of the wreck, there is nothing in Titanic Belfast actually from it. You’d think that having gone to all the expense of building this shiny edifice that keeps the story alive, to the benefit of those that bring the lucrative bits and bobs up from the seabed, they would have donated something. A rusty teaspoon maybe, or a barnacle encrusted kharzi seat? There is a lifejacket and deckchair, but in my book they don’t count as they were floating on the sea during the rescue. Nice try, but no cigar…not even a soggy one.

Another thing that is not really given airspace in the exhibition is that when the ship was built in Belfast, between 1909 and 1911, it was indicative of the discriminations that would bubble up into the troubles sixty years later. Apparently, the builders were predominantly Protestants, the Catholics being deliberately excluded from the workforce, as they were in many public and commercial commissions and positions. When it sank there was a certain amount of schadenfreude, the Catholics blamed it on shoddy Protestant workmanship.

As a taxi driver told us, the Catholics certainly couldn’t be blamed for this one, they were busy up north building the iceberg.

* The Oompa Loompas are the little orange men in Charlie and The Chocolate Factory. Apparently, they have Orangemen in Belfast too, a sort of Technicolor version of the Masons but with less of a wacky sense of humour.

** Naturally I did end up in a Wetherspoons in Belfast. Cheap beer, half-decent food…why wouldn’t you?

*** I did fall out with one very rude woman who swiftly whipped away a bar stool I was resting my feet on, without so much as a by your leave. Although in her defence, she was English.